Wild Water Buffalo

The Vanishing Herds

The Wild Water Buffalo

Anwarudddin Choudhury

Gibbon Books and The Rhino Foundation for Nature in North

East India

2010

Wild Water Buffalo brings forth two memories. One was the

first clear sighting at Kaziranga - along the highway - with a friend. Recall

staring at its magnificence in silence for more than few minutes; we did not

stop as much for the Asian Elehpant or the Indian Rhinoceros. The horns seemed ‘unreal’.

Second is its popping up in discussions during Baghmara days. Locals mentioned

of Rewak being the place where Wild Water Buffalo used to occur and the only

place in Garo Hills where it was common and a senior forest department official

had shared – more than once - of his having seen a herd of 20 some years back

on the plateau in Balpakram NP.

This query on Garo Hills is addressed in the book.‘A bull was ordered by the authorities to be shot dead

for killing human beings near Rewak in present South Garo Hills district in

1935. Interestingly, in the same area, the authorities had to allow shooting of

another bull for killing several human beings in 1975. The head with both horns

intact is on display at the Forest Museum, Shillong’. It quotes papers from

JBNHS in 1940s mentioning Rewak as a ‘renowned for buffalo with fine horns’.

The author estimates the current population of South Garo Hills to be less than

50. The book also boasts of some interesting images and

sketches.

The author looks at the species with details and the

result is a very interesting read for one interested in forests. From

historical records like in the Baburnama which are referred to as ‘perhaps the

earliest written documentation on the Wild Buffalo’ to the books like

Blanford’s Fauna of British India (1891) and The Maharajah of Cooch Behar

(1908). From distribution in multiple states in India to the status in Thailand

– entire range of the species.

Author’s familiarity with the region is brought out when

he shares species’ numbers depicting the downslide as also issues like the

species being hunted and it’s meat mixed with that of deer to enable selling at

a higher price. This is in context of Manas but there are interesting notes on

other Protected Areas of Assam as well.

Along with other conservation challenges the author lists

Big Dams stating hydrodynamics modification may pose the greatest – but

potentially most avoidable – threat to flood plain ecosystems including

Kaziranga. Interestingly plantation of trees has been listed as well! The

eagerness of forest department to convert the grasslands (even inside Protected Areas) to tree cover is a threat to grassland

specialists like the Wild Water Buffalo and Bengal Florican.

The chapter on Ecology and Behaivour talks about its

interaction with other species. Amongst mammals it has been observed to be at ease

(graze, wallow) with Indian

Rhinoceros, Asian Elephant, Hog Deer, Swamp Deer and Wild Boar in Assam. In the

Central Indian forests it has been observed with the Blue Bull as well.

Bibliography is of interest to anyone wishing to pursue

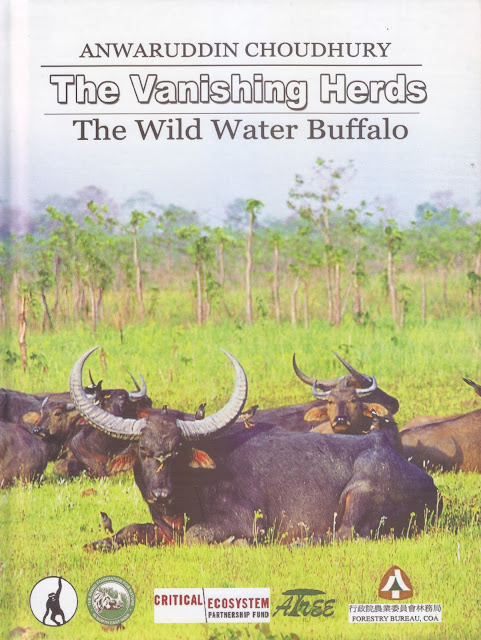

the topic. Images of the species in wild and trophies from multiple locations

help put across its splendor, and there are few sketches as well. Tables list

the trophies with their measurements and remarks and there is one which lists Protected

Areas where the species has gone extinct during the 20th Century.

This is a species which of which today we know of more sub

populations than a decade ago – as in having discovered previously unknown ones.

The species has thus succinctly conveys that while we have lost the art of

living in harmony with nature; nature retains its skills of presenting

surprising despite how we treat it.

Janaki Lenin in her recent article Long way to go to conserve India's Wild Water Buffaloes states: 'India has the largest population of Wild Buffaloes, an estimated 3,000, mostly in the north-eastern state of Assam and a smattering in central India. That might sound like a lot, but they are beset with problem. Water buffaloes need water to wallow and grazing land. They are losing both.'

Few questions surfaced on reading the book, share two below:

Given that Kaziranga has more than half of the species population

– like is the case for the Indian Rhinoceros - can we ensure that it does not

become an island? Can we meet the immediate threats from tourism, roads and

other manifestations of development?

Why do we have this ‘silly’ urge to tame and manage nature?

The author shares how the forest department converts grasslands to woods. Some

days back, I recall reading of how the natural regeneration in Kuno WLS (Madhya Pradesh) is being managed to

‘retain grasslands’ for the much awaited large cats. As if this was not enough

it was praised as the best grassland management in the country!

Comments

Post a Comment