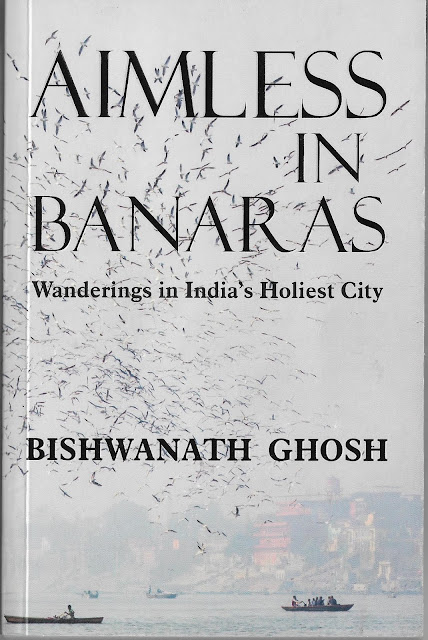

Aimless in Banaras

Aimless in Banaras: Wanderings in

India’s Holiest City

Bishwanath Ghosh

Tranquebar, 2019

ISBN 9789389152005

Thanks are due to the team at First

Post.

Couple of months ago,

as I discussed Banaras with a friend, she referred to its famed Ganga Jamni

tehzeeb. The violence and acrimony we come across today is not what the place

stood for, she added. Hatred, I agreed with her, was not what the town represented.

However, I argued that the town was also not only about love and harmony, and

that people existed between the two extremes. This other side of the story, in

sync with society’s shying away from difficult topics attitude, is seldom

discussed. Hatred.

During school years,

I used to accompany mumi to her parents’ place each summer. There, at

the heart of the town, it seemed that all the reverence was reserved for the

sounds emerging from the temple. The calls from masjid were frowned upon, and

decidedly so. While the Pandit was suffixed with a Ji, the Mullah

was prefixed with a Hindi slur. The other day, I asked mumi if anyone in

her family had muslim friends. She was uncharacteristically quick in responding

with a “no”.

Today, I live in an

old, large campus in Banaras, which also houses a Mazar. The language used

by some of my colleagues to refer to Muslims on a regular basis, will not find

place on this platform. It was only the other day that a colleague mentioned how

the demolition of buildings near the Kashi Vishwanath Temple had led to a sad

situation. As I wondered why, he added that it had enhanced the visibility of

the Gyanvapi Mosque abutting the temple. The mosque was better hidden, he said.

Talking of caste, the

privileged young I came across in Gujarat used to pretend it did not exist. In

Banaras they are proud and loud about it.

Ghosh, to his

credit, does not shy from talking about this side of the town in his book

Aimless in Banaras: Wanderings in India’s Holiest City. He mentions how they Babri

Masjid demolition, and the period that followed, changed the fabric of the town.

He takes note of the razing of homes for a corridor that will connect the Kashi

Vishwanath temple to the river. He also touches upon Pujaris flying

across the globe to conduct rituals, and looking down upon other pujaris.

And, of course caste. All these he does in a straight forward manner.

Ghosh isn’t afraid

of referring to the much-hyped and praised evening arati on the river as

“a sham”. The arati – as it is currently performed on select ghats

- is an act Banaras can do without.

Ghosh quoting someone,

who stayed in the town for few years, writes “Banaras taught me lessons

which no book could ever have taught”. This line holds true for me as well as

it perhaps does for many others. The town is special, and depending on how one

experiences it, it is a place for music, religion, faith, history, mythology, exotica, Sanskrit,

spirituality, and much else. Few remain

untouched by it; most are deeply influenced by it in myriad ways.

Unsurprisingly, much

has been written about Banaras. To touch upon a few - Diana L Eck’s ‘Banaras: City of Light’ remains a seminal book on the town. Besides,

Pankaj Mishra’s ‘The Romantics’ too is popular. There, of course, is

Kashinath Singh’s ‘Kashi Ka Assi’, considered a bona fide modern-day

classic on the subject. Amongst those published in recent years, Saba Dewan’s ‘Tawaifnama’ has received favourable reviews,

while Aatish Taseer’s ‘The Twice Born’ failed to make the cut somehow. Varsha’s Varanasi, by Chitra Soundar, a book primarily

catering to children, proved to be a disappointment as well. Evidently, reading

a good book on Banaras is fascinating, but writing one is anything but easy.

In case of Aimless in Banaras:

Wanderings in India’s Holiest City, the book not only seem to suffer from a lack

of attention to detail but also from Ghosh’s affinity for the clichéd. When

Ghosh writes about the Ramleela he

generalizes, “typically takes place over nine nights . . but in Banaras

performances are spread over a month”. Generalization seldom works. Similarly, when

he writes about sarees, he appears to have not taken the pain to delve deeper

into the subject. He also generously uses superlatives about a place which, to

put mildly, is not easy to comprehend; “the oldest”, “the newest”,

“the most popular” and “the best-known”.

As I looked up the

book at a book-store that I frequent in town, two people there mentioned an

error it carried. Banarasis, from the little I know, take themselves and their

town seriously. They pointed out that Ghosh has mistakenly mentioned Gaya Singh

as the only character in Kashinath Singh’s Kashi Ka Assi whose original name

has been retained. They dispute this claim made by Ghosh by adding that the original

names of most characters have been retained in Singh’s book. I corroborated

this claim by looking up online review, a couple of which pointed to the error.

Talking of ghats he writes, “There

is something depressing about the ghats that lie north of Dashashwamedh. . .

They are poorly maintained . . This segment is also Benaras, but this is not

where all the actions take place”. My regular walks along the ghats bring

out that this is the less touristy stretch. Friends from the town, I walk with,

add that this stretch is what remains of the asli Banaras. Some of the

lines appear outright strange. “I have never come across a human swimming

across its entire breadth, at least in Banaras” or “In Banaras no one

preaches to you”. And one wonders why he could not stay away from the, too

oft-repeated, quote by Mark Twain.

Varun Grover, during

a recent interview, mentioned that Banaras has always been viewed through the eyes

of the white man. You need time to break through the clichés that we have been

fed through this gaze. Ghosh appears to

have fallen in this trap.

The other day, a friend

and I walked the lanes of Banaras to our destination in the Chowk locality for

some malaiyo. He asked how, in the famed labyrinth of these lanes, I

find my way. Do I seek help from maps on the web or had I learnt to identify

landmarks amidst the maze or else? None, I responded; Banaras gets into one’s

system. Learning to find one’s way in its lanes is akin to learning to cycle or

swim. Once you know the lanes they take you around. Perphas , in the case of Ghosh,

Banaras has not gotten into his system.

"...how in the famed labyrinth of these lanes, I find my way."

ReplyDeleteWalk through them, long and often, I think. Get accustomed to the smells and sniff your way through.

Hmmm . . These days itching to get there . .

ReplyDelete